|

Aquatic Gardens

Ponds, Streams, Waterfalls

& Fountains:

Volume 1. Design & Construction

Volume 2. Maintenance, Stocking, Examples

V. 1

Print and

eBook on Amazon

V. 2

Print and

eBook on Amazon

by Robert (Bob) Fenner |

|

The single most important thing to

know about aquarium salt is that it isn't a cure-all. While salt

can fix some problems, it won't fix them all, and in some cases it

can actually create problems all its own. So before adding salt to a

freshwater aquarium or pond you need to be sure it'll do some

good.

In this article we'll start by

looking at why aquarists use salt so readily, even though it isn't

always an appropriate treatment or additive. We'll then look at

when salt is an appropriate treatment and how much to use. We'll

then round off this article with a look at the risks associated with

using salt, and why regularly adding salt to a freshwater aquarium or

pond isn't necessary.

Some history

To understand why aquarium salt is

widely sold, and why fishkeepers use salt so freely, you need to know

some aquarium history.

Up until the 1980s, most fishkeepers

believed that water changes should be minimised. 'Old water'

was thought to be good for the fish, so water changes were often

limited to around 20% per month. With such small water changes, nitrate

levels were often very high. At high concentrations, nitrate can be

toxic to fish, but sodium chloride reduces the toxicity of nitrate.

While aquarists didn't necessarily know this, what was observed was

that fish were often healthier in tanks with a bit of salt added to the

water.

From the 1980s onwards, the value of

'old water' was called into question. Compared to preceding

generations, aquarists were now keeping much more delicate fish

species, such as Malawian and Tanganyikan cichlids, and it was quickly

discovered that they were very sensitive to high nitrate

concentrations. It was soon realised that not just cichlids but all

fish benefitted from regular water changes, and now it is recommended

that aquarists change at least 20-25% of the water in an aquarium per

week.

Now that nitrate levels are kept low

through water changes, the usefulness of salt in reducing the toxicity

of nitrate is much diminished. Indeed, as we'll see later on, any

slight benefits it still has in this regard may be outweighed by the

stress it can cause fish that are intolerant of constant exposure to

salted water.

A note on concentrations and

doses

Vets and aquarium health experts

usually describe the amount of salt required in grammes per litre.

Rather conveniently, a level teaspoon contains about 6 grammes of salt,

so a dose of 2 g/l can be translated as 1 teaspoon per 3 litres. If you

don't know the capacity of your aquarium in litres, multiply by its

capacity in US gallons by 3.79. For example, a 55-gallon aquarium has a

capacity of 208 litres.

Baths versus dips

Salt is used in two different ways,

baths and dips. A 'bath' means the fish is constantly exposed

to the salt. In other words, the salt is added to the aquarium. A

'dip' is something the fish is briefly dipped into, typically a

bucket of aquarium or pond water into which some salt has been

added.

How to add salt to an aquarium

Don't add the salt directly to the

aquarium. Instead measure out the amount you need into a jug, add some

warm water, stir until its all dissolved, and then slowly pour the salt

solution into the aquarium. Low salinity solutions can be added to the

aquarium in one go, but if the required salinity is more than 2 g/l, it

is best to add the salty water in portions across several hours. This

will give the fish some time to adapt to the change in salinity.

Suppose you're treating whitespot

in an aquarium measuring 208 litres (55 US gallons). The required salt

concentration is 2 g/l, or 416 grammes for the whole aquarium. This

would be first measured out using kitchen scales, then tipped into a

jug, dissolved in warm water, and finally poured into the aquarium.

How to do a dip

Although they are very useful, dips

can be risky if not done carefully. Most fish find saltwater dips

intensely stressful, so the fishkeeper must watch the fish carefully

and remove it if it shows any signs of severe distress, such as rolling

over onto its side.

Start by putting some pond or aquarium

water into a bucket or some other suitable container large enough that

the net holding the fish can be submerged easily. Stir in the required

amount of salt. In the case of leech removal for example, a dosage of 9

grammes per litre would be required. So if the bucket used holds 15

litres of water, 135 grammes of salt would need to be added.

Once the salt is fully dissolved, the

fish will need to be netted out of the pond or aquarium, and then

lowered carefully into the saltwater dip. The fish will need to be

completely submerged, so it's important that the net being used is

large enough to hold the fish comfortably. While the fish is being

dipped, keep an eye on both the clock and on the fish. Depending on the

type of fish and its size, dips can last anything up to half an hour.

Generally, the longer the better, but the tolerance of the fish will

likely place an upper limit on how long it can be safely dipped

for.

After the dip is completed, take the

net back to the pond or aquarium, and rest the fish in the water until

it is fully recovered. Once it looks settled, release it from the net.

Discard the dip water after use.

What salt

treats

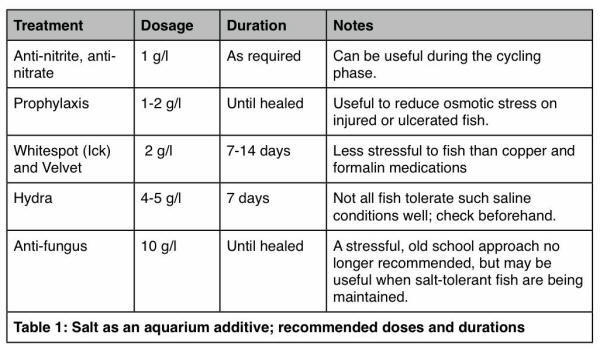

(1) Reducing

nitrite and nitrate toxicity

Salt reduces the toxicity of nitrite

and nitrate. While nitrate rarely reaches dangerous levels in a

properly maintained aquarium, nitrite levels above zero are commonly

seen in overcrowded or immature aquaria. As a short term measure, the

addition of 1 gramme of salt per litre of water will reduce

stress and minimise the problems caused by stress, such as finrot.

Note that the use of salt doesn't eliminate the need to fix

whatever problems are causing the non-zero nitrite level.

(2)Prophylaxis after injury

A prophylactic treatment is one

that prevents rather than cures disease. When fish are injured they

can succumb to secondary infections such as finrot and fungus. By

maintaining an injured fish is slightly salt water, osmotic stress is

reduced, and this prevents the fish from becoming weakened. This in

turn ensures its immune system works properly, and so the chances of

secondary infection are reduced. Add salt at a dose of 1-2 g/l.

Maintain this level of salinity until the wounds are healed.

(3) Against

whitespot and velvet

The free-living stages of ciliate

protozoans including whitespot (ick) and velvet are less tolerant of

salt than are fish. When the cysts burst and the free-living stages

enter the water, they are dehydrated by the salt and die. The

recommended concentration is 2 g/l, and this should be maintained for

at least 7 days, and preferably 14 days. To speed up the emergence of

the free-living stages, the water temperature should be raised to at

least 28 degrees C (82 degrees F) and ideally 30 degrees C (86

degrees F). Because warm water contains less oxygen than cool water,

increase aeration and/or water circulation if the fish show signs of

respiratory distress, such as gasping at the surface.

(4) Kill

hydra

Hydra is a tiny,

anemone-like animal that normally does little harm but can be a pest

in breeding tanks because its stinging tentacles can catch and eat

fry. A concentration of 4-5 g/l will kill Hydra within a week,

but note that soft water fish in particular may not tolerate such

salty water well. If necessary, remove the fish from the infested

aquarium while it is being treated.

(5) As a

fungicide

Fungi are mostly intolerant of

brackish and saltwater conditions, and moderately high concentration

of salt have been used to treat fungal infections. A concentration of

10 g/l is required, about 30% the salinity of normal seawater. This

is well above the tolerances of most freshwater fish. So while this

treatment can be effective, it is best reserved for those freshwater

fish with a high tolerance of brackish water: livebearers, gobies,

pufferfish, tilapiine cichlids, killifish, and so on.

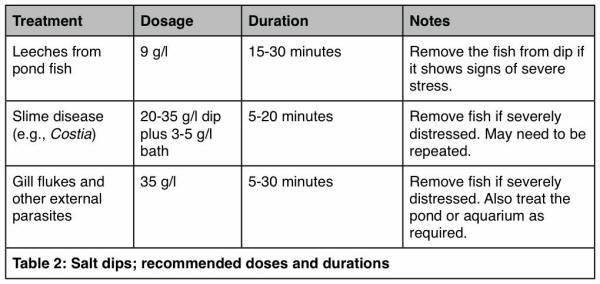

(6) Against

leeches

Strongly saline water is useful

as a treatment for leeches. Rather than as an addition to the pond or

aquarium, the salt is used at a concentration of 9 g/l to create a

dip. The infected fish is dipped into this solution for up to 30

minutes, by which point the leeches will detach themselves from the

fish. The leeches can then be destroyed and the fish returned to the

pond or aquarium. Because leeches leave behind open wounds, some sort

of prophylactic treatment against secondary infections will probably

be required.

(7) Against

slime disease

Slime disease is caused by a

variety of parasitic protozoans such as Ichthyobodo

(Costia) spp. that cause the skin to produce unusually large

quantities of mucous. Salt needs to be used in two ways to treat

slime disease. Firstly, the salinity of the aquarium needs to be

raised to about 3-5 g/l, and the aquarium left this way for 7-14

days. Secondly, on the first day of treatment, the infected fish

should be dipped into a strongly saline solution containing 20-35

g/l. This will help clear up the mucous and speed up recovery, but

such salty dips are very stressful for most freshwater fish. While

dips of up to 20 minutes should be safe in most cases, if the fish

shows signs of severe stress, such as rolling onto its back, it

should be immediately returned to the aquarium.

(8) Against

anchor worms, lice and other external parasites

Exposing freshwater fish to

saltwater conditions for varying periods of time can be a good way to

shift external parasites such as fish lice and anchor worms. The

required concentration is 35 g/l. However, this is a risky treatment

because freshwater fish do not tolerate sudden and extreme increases

in salinity very well. Large fish (such as adult goldfish) and

salt-tolerant fish (such as tilapiine cichlids) tolerate saltwater

dips between than small fish and soft water fish. It's also worth

noting that removing parasites this way doesn't prevent

re-infection, so some treatment of the pond or aquarium will be

necessary.

What salt

won't do

(1) Salt

doesn't magically make an aquarium a better

place

There's absolutely no need to

add salt to freshwater aquaria except under the circumstances

described above. At best, it'll do nothing of any value at all.

At worst, it'll stress salt-intolerant fish, making them more

vulnerable to disease and less likely to live to a ripe old age.

(2) Salt

won't raise pH and hardness

By itself salt merely raises the

salinity, not the pH and hardness. Marine salt mix can be used to

raise pH and hardness since it contains not just salt but a variety

of other mineral salts as well, but only in aquaria where

salt-tolerant freshwater fish are being kept, such as guppies or

mollies.

(3) Salt

won't treat finrot (and isn't that useful against fungus

either)

While it has some preventative

value, as mentioned above, salt has little impact on opportunistic

bacterial infections once they are established. To treat these a

proper antibacterial or antibiotic medication will be required. Salt

will treat fungal infections, but as described earlier, the required

concentration is so high that it isn't a safe treatment for most

freshwater fish.

How salt can

cause problems

(1) Malawi

Bloat

Malawi Bloat is a Dropsy-like

syndrome typically observed among Malawian and Tanganyikan cichlids,

hence the name. Affected fish are bloated, have trouble breathing,

become lethargic, and eventually die. There is no reliable cure,

which is why prevention is so important.

Several causes of Malawi

Bloat have been identified, including the use of salt in Rift Valley

aquaria in the mistaken belief that salt hardens the water and raises

the pH. Salt does neither of these things. To create hard water

conditions a proper Rift Valley salt mix needs to be used, either

purchased ready made, or

mixed at home from Epsom salt, baking

soda and marine salt mix.

(2) Stresses

soft water fish

Fish and plants from

mineral-poor waters do not appreciate being kept in slightly saline

water conditions. One reason aquarists got away with adding salt to

freshwater tanks in the past was that the species being kept were

usually hard, adaptable species able to adjust to a range of water

conditions. But many of the most popular fish today, like cardinal

tetras and rasboras, come from soft water habitats. Short term exposure

to low salt concentrations across a few days or a couple of weeks

won't do them any harm, but constant use of salt in their aquaria

could cause problems.

(3) Stresses plants

Like freshwater fish,

plants tolerate salt to varying degrees. Low concentrations, up to 2

g/l, won't do them any harm, but above 5 g/l most freshwater plants

will be stressed and eventually killed.

Addendum: Epsom

Salt; usage

Epsom salt or magnesium

sulfate (or magnesium sulphate in British English) is a mineral salt

widely sold in places like drugstores as well as various vendors

online. It is used in two ways within the hobby:

1. To raise

general hardness.

Epsom salt may be used

on its own or as part of a Rift Valley Salt Mix of the sort useful in

tanks holding hard water fish such as Mbuna, Tanganyikan cichlids,

Central American cichlids and Central American livebearers. To create

very hard water around 20 degrees dH, a dosage of around 1 tablespoon

Epsom salt per 5 US gallons/20 litres. For more, read A

Practical Approach To Water Chemistry.

2. To treat

swelling, constipation, dropsy, pop-eye, etc.

Epsom salt is a mild

muscle relaxant that can be useful when treating swelling and

bloating. It works as a laxative, with a dosage of 1-3 teaspoons per

5 gallons/20 litresbeing recommended depending on the severity of the

case. Raising the temperature by a degree or two often helps by

speeding up the fish's metabolism, and the use of fibre-rich

foods such as cooked peas is extremely helpful.

Why Epsom salt helps

with dropsy and pop-eye is less clear, but it can be helpful and is

worth using alongside whatever antibiotic treatments are being used.

Possibly the Epsom salt helps to draw fluid out of the swelling. In

any case, the recommended dosage is again 1-3 teaspoons per 5

gallons/20 litres.

FW salt

article 2/5/10